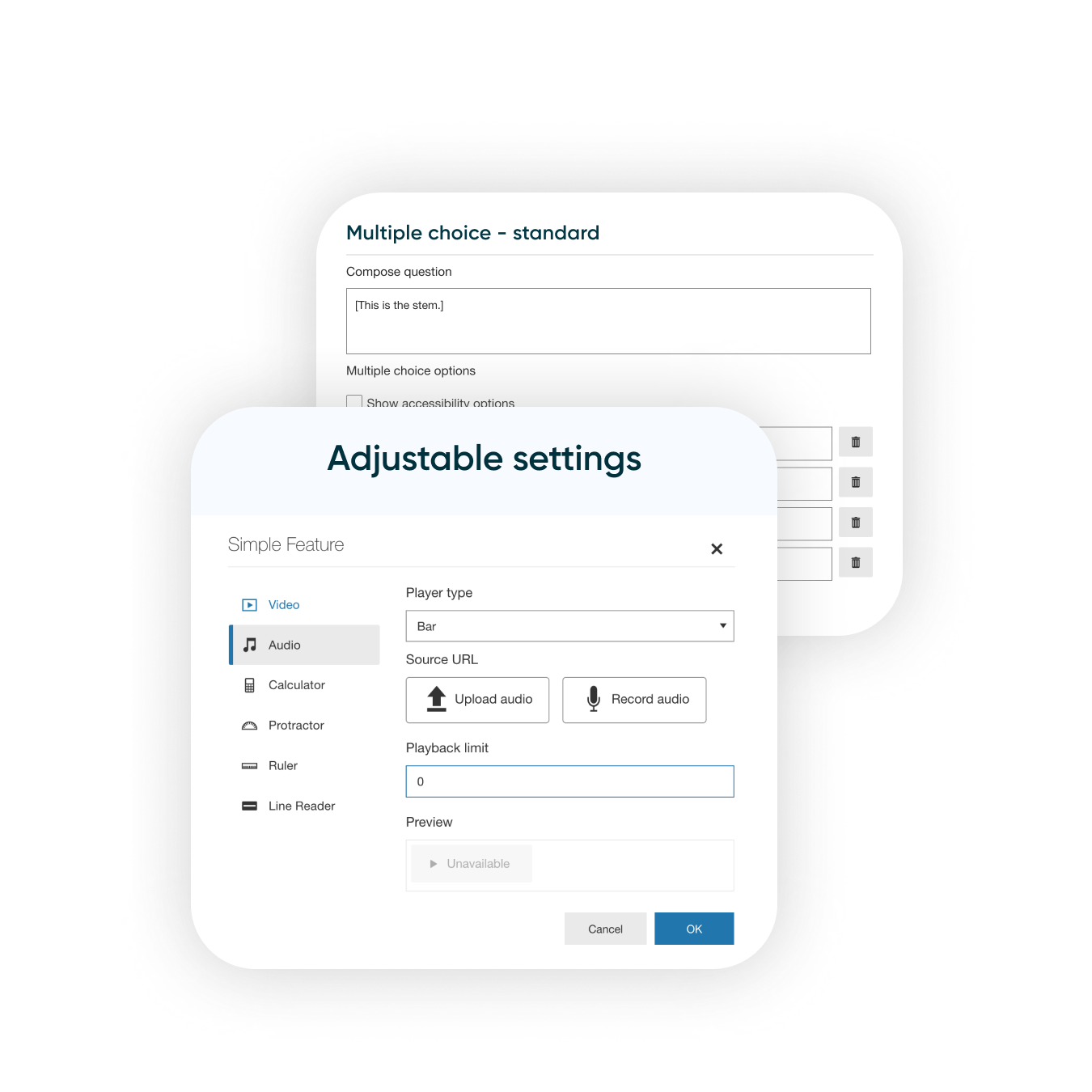

Variety is the spice of learning

With 50+ prebuilt types of assessment questions and interactives to choose from across 9 categories, Learnosity opens up new possibilities to engage learners of all levels and disciplines—from STEM to visual arts to workplace training and beyond.

-

Multiple choice

Create MCQs that are as simple or sophisticated as you like with support for flexible layouts, images, audio, distractor notes, math content, and more.

-

Fill in the blanks

Easily create fill in the blanks questions using text, images, dropdowns, and drag and drop functionality.

-

Classify, match & order

Pair or order words, phrases, pictures, or symbols to see how learners create associations between lists of items.

-

Written, audio & visual

Give learners the tools to respond in their own words with short text, essay-length text, images, file uploads, and mobile-friendly video and audio capabilities.

-

Highlight

Illustrate your point with an assortment of interactive visual question types such as drawing, shading, highlighting, and hotspotting.

-

Math

Create complex, open-ended math assessment questions with multiple possible answers and have them auto-scored instantly by our custom-built math-scoring engine.

-

Graphing & charting

Generate sophisticated interactive charts, graphs, and number lines with ease then accommodate multiple possible answers with smart scoring.

-

Chemistry

Set and score advanced questions on molecular, empirical, and condensed structural formulas and give learners a flexible on-screen keypad to input responses.